— The Scriptorium —

Guildwater News Archive

THAYER SARRANO

(Zürich, Switzerland)

October 04, 2016 (Tuesday) - Thayer Sarrano visits Zürich, the fifth of six Swiss dates. Thayer is accompanied by Ted Kuhn (bass) and Jason Nazary (drums). They play the Henrici. When it came to Zürich, we Guildwater Scribes knew we would have trouble choosing which subject about which to write. We originally wanted to speak about the Dada art movement, but decided even prior to Thayer's Tour Europa that we didn't want to write at all about the First or Second World War. We initially settled then on Huldrych Zwingli, whom you will discover at the bottom of this scroll entry. Even before that though, in our investigations about other places, we got sidetracked mightily, and simply could not throw away some of the materials we dredged up. This particular parchment should prove long, and varied in subject -- everything from Zürich to Rudolph the Scribe, from alchemy, to Zwingli. Here goes: the city of Zürich gives its name to the outlying canton, of which it is the capital. Like neighboring Winterthur, it was early on the object of Roman interests and settlement. After the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, this area found renewal under the Carolingians. In the mid-800s, one of Charlemagne's grandsons, Louis the German, who inherited East Francia, which was the easternmost portions of the Holy Roman Empire, endowed for his daughter Hildegard's sake the convent of Fraumünster. Over time, just as the Abbey of St. Gallen ruled its outlying areas, so did Fraumünster and its Abbess play a central role in the politics of Zürich. Across the 1300s, the authority of the convent slowly diminished, with the rise of the city guilds. Though neither as extensive or as early as St. Gallen, Zürich, in that late medieval period, did show cultural prowess. Two manuscripts interest us here.

The first is the Codex Manesse, now found at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, but which was originally produced locally in Zürich, under the patronage of the affluent Manesse merchant family, in the first half of the 1300s. It is essentially a medieval songbook, like the Carmina Burana, only in the case of the Codex Manesse it is the largest and most comprehensive medieval collection of German minstrel (minnesinger) poetry. Such medieval poets and songwriters became the very stuff of legend and folklore, even the source of Richard Wagner's opera Tannhäuser. The work of the real Tannhäuser is found in the Codex Manesse. The Codex is written in Middle High German. It includes songs and poetry attributed to emperors, kings, and other assorted nobility, as well as many long-forgotten writers bordering on pure anonymity, save for a name. Two illustrations stand out as particularly dear to us Guildwater Scriveners: "Der Tugendhafte Schreiber" ("The Virtuous Scribe") (305r), and that great unsung hero of the medieval period "Rudolf der Schreiber" ("Rudolph the Scribe') (362r) (Pictured Above). Save for the absence of a water cooler, and the black Zebra Grappling Mats of our Employee Recreation & Wellness Center, this is essentially a photographic rendering, down to the minutest detail, of a typical day at our Guildwater office suites. Our venerable Abbot got so carried away upon seeing this, he decided to grant Rudolph posthumously our honorary "Employee of the Millennium Award." In addition to parking privileges, Rudolph is entitled to dress casually on Tuesdays for the better part of this century.

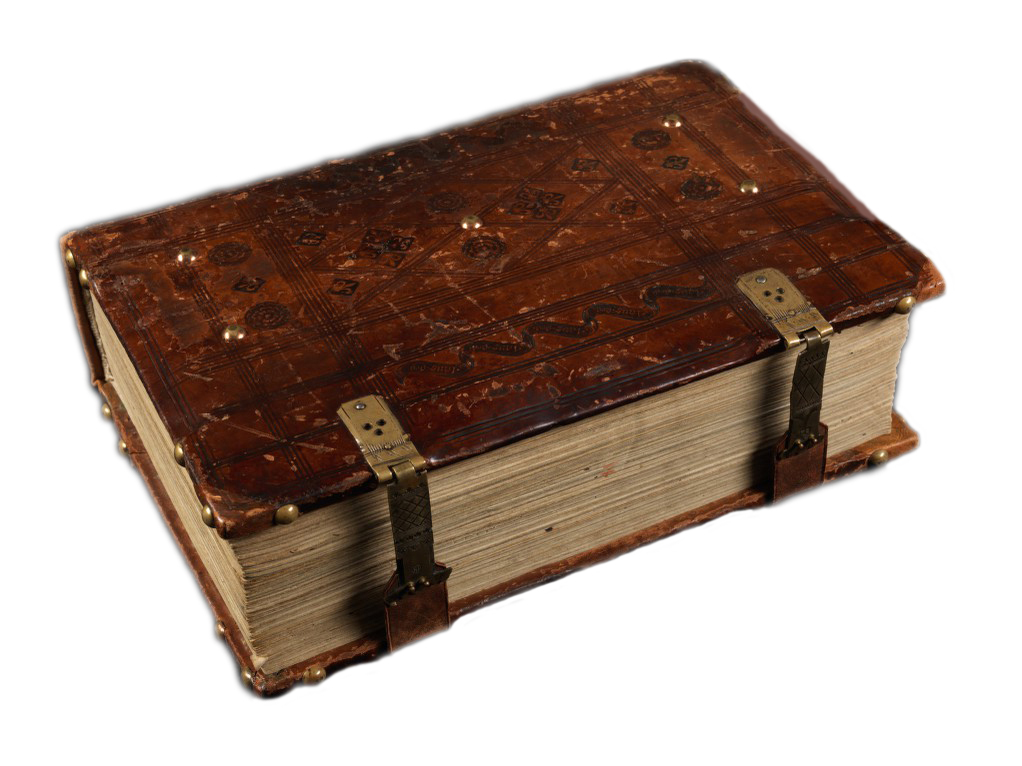

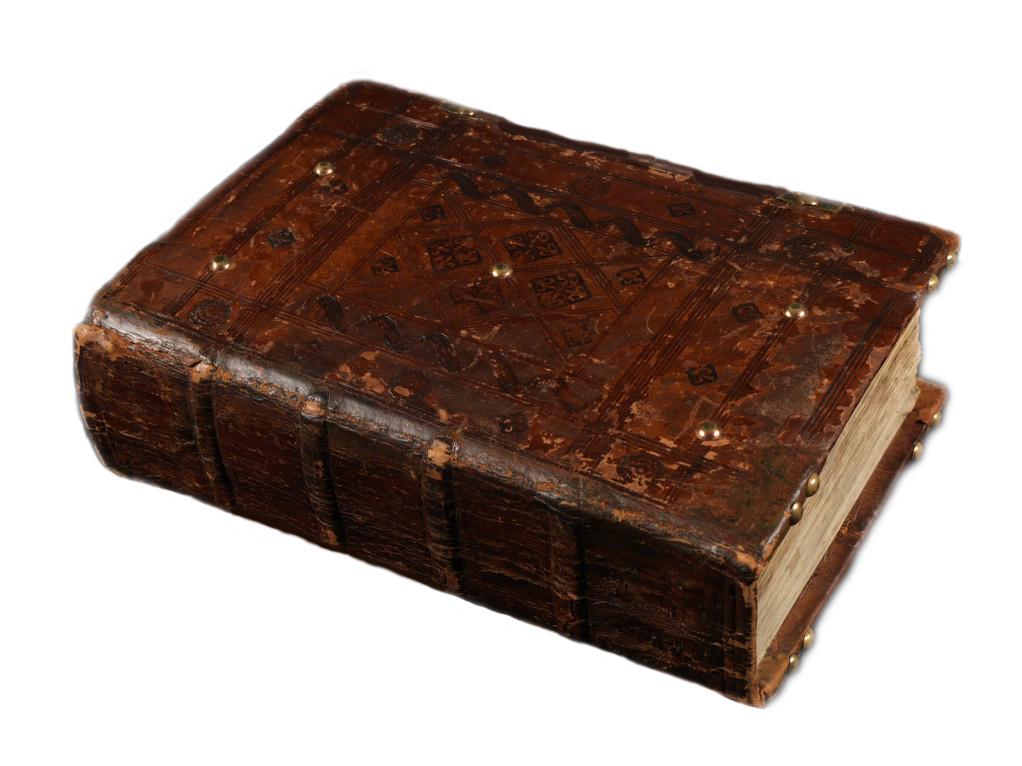

(Source: Zürich Zentralbibliothek)

The second text that interests us is a copy of the fifteenth-century text Aurora consurgens, as found in the Zürich Zentralbibliothek (Ms. Rh. 172). It is combined in manuscript with a few other treatises of the late medieval period. The Aurora and the other included works are a curious breed. They are alchemical treatises. In the popular imagination, alchemy is often reduced to the quest to turn base metals into gold, sometimes described as the "philosopher's stone." It was / is more than this alone. Alchemy also endeavored to discover the magical elixirs of life, rejuvenation, and even immortality. As far-fetched as some of those goals may seem from the perspective of modern science, it should not be overlooked that these quests often involved intense experimentation -- the combining of various substances in the hope of achieving the transmutation of materials from one form to another. In the case of the Swiss cantons, Paracelsus (1493-1541), born Philip von Hohenheim near Einsiedeln, in the Canton of Schwyz, the neighbor of Zürich, located on the southern coast of Lake Zürich (Zürichsee), would have himself been familiar with the Aurora Consurgens (though not necessarily this particular copy), as well as other texts of the traditions of hermeticism. In its own peculiar way, the fascination and experimentation of alchemy of this and earlier eras would contribute to the eventual development of the scientific method, through later astronomers and early practitioners of "science," including, among numerous others -- Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, Francis Bacon, Descartes, Blaise Pascal, and Isaac Newton, the latter of whom was intensely interested in alchemical pursuits. Paracelsus and the experimenters of his age were, in many respects, the necessary precursors of the later Scientific Revolution.

Huldrych Zwingli was born in 1484 the son of a free farmer, who served as a magistrate in Wildhaus, in the Canton of St. Gallen. Through his uncles, Zwingli had connections to the Catholic Church, which at that point had not yet been split by the Reformation. Zwingli would play his role in that very development. It is anecdotal, but it is worth noting that, unlike Martin Luther in Saxony, and the Frenchman Jean Calvin in Geneva, Zwingli's disposition was warm, open, and friendly. Yet, even though he ranked among their number as a major reformer, Zwingli was the only one of the three not to establish his own denominational church. He probably would have, had his life not been cut short by events. One uncle was, initially, a local priest. Another was an Abbot in the Thurgau canton. From his initial schooling, Zwingli moved on to studies in Basel and Bern, where he was inculcated with the educational standards of scholasticism, which meant heavy doses of St. Thomas Aquinas. Zwingli demonstrated musical talents early on, which interested the local Dominican Order, of which Aquinas had himself once been a member. But, unlike Luther, Zwingli would not embrace the monastic life, even that of a mendicant order. He was dissuaded by both his father and an uncle. Zwingli attended the University of Vienna for a time in the late 1490s, but finally obtained his degrees at the University of Basel in the early 1500s. He also then received clerical ordination. Zwingli obtained a post in the city of Glarus in the canton of that same name. Beyond his sermon duties, Zwingli read widely -- the classics of antiquity, and the patristic texts of the early Church Fathers. Zwingli taught himself Greek and Hebrew, with the intention of reading the Bible in the original. He corresponded with the influential Dutch humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. While in Glarus, Zwingli also served as a priest for local Swiss mercenary troops. The Swiss Cantons found themselves entangled in the struggles of the Austrian Habsburgs and the French Valois kings for dynastic control of the Italian peninsula. Zwingli was an eye-witness to the carnage at the Battle of Marignano near Milan in 1516, where some 10,000 Swiss mercenaries died. Even before this, Zwingli had written an allegory entitled The Story of the Ox, which criticized the mercenary system. The Swiss cantons were portrayed as a "peaceful ox," playing upon a theme familiar to the period, depicting the Swiss as an ox or bull (Schweizer Stier), the pronunciation of which would impact the English-speaking world's use even today of the word "Swiss," as in Switzerland. After Glarus, Zwingli came to be the Leutpriester or "People's Priest" of Einsiedeln in the Canton of Schwyz. There, as Luther had criticized the sale of papal indulgences (or the purchase of the forgiveness of sins) in Wittenberg in 1517, Zwingli did likewise in 1518. Yet, whereas Luther had been ordered to desist by Pope Leo X, Zwingli was, it seems odd, actually supported in his critique, by the nearby Bishop of Constance. It appears the motivating factor was that Pope Leo X did not wish to alienate the Swiss Cantons, especially the role that their mercenaries played in the papal armies of the Habsburg-Valois Wars of that period, particularly in the Italian Peninsula. From Einsiedeln, Zwingli applied for and received a similar post as priest at Zürich's Grossmünster. This was the largest pulpit platform he had yet obtained.

(Photo: Aak47)

Inspired by Erasmus and Luther, Zwingli embarked on his "True Divine Scriptures" sermons across 1519 and 1520. Discarding centuries of Church-approved Biblical commentaries, Zwingli preached straight from the Bible itself, claiming that: "I began to test every doctrine by this touchstone." He offered these particular sermons in the Oetenbach Convent of Zürich. Revealing how "revolutionary" his undertaking was, Zwingli, first, sought the approval of Zürich's City Council. The Council was torn, and deferred authorization to the Bishop of Zürich, who granted his approval to Zwingli's sermon-cycle. Emboldened, Zwingli searched the Bible for precedents regarding numerous Church practices: vestments, the veneration of Saints, the concept of Purgatory, tithes, fasting, clerical celibacy, and the use of sacred music and images in churches and cathedrals. It must be remembered that this was the height of the Renaissance period, the time in which Michelangelo, to take but one example, had finished his frescoes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling in 1512. It was also the era in which the new St. Peter's Cathedral, whose very cost encouraged the sale of Indulgences, was under construction in Rome, since 1506. All this was undertaken under the guidance of Pope Julius II, the last pope to lead troops into battle. And, in Zwingli's own reform days, none other than members of the Medici family of Florence sat upon the papal throne -- Leo X until 1521, and another in Clement VII in the same decade. As the Catholic church obtained new heights in art and architecture, many reformers questioned the profound sumptuosity. This was but one part of a broader criticism of other Catholic practices, for which reformers like Zwingli could find no clear scriptural basis. During Lent of 1522, Zwingli gathered with some fellow Zürich locals and, even though he did not himself participate, broke fast, eating sausage. Zwingli's sermon "On the Choice and Freedom of Foods" was duly printed and circulated. And, as the duke of Saxony extended his protection to Luther, here the Zürich city council embraced Zwingli's proposed reforms in 1522. Local priests were required to preach only from the Bible. Mass was forbidden in 1524. Images were removed from Churches. Organs wer silenced. There was the dissolution of monastic house, including Fraumünster, whose Abbey had once ruled the city centuries before, as originally established by Louis the German in the Carolingian period.

(Photo: Roland zh)

The list reforms went on. More debates followed with other reformers, from other cantons, and beyond. Zwingli and Luther himself debated the theology of the Eucharist at the Colloquy of Marburg in 1529. They found little common ground. It is difficult to imagine, now, how explosive such topics were for a Europe that up until that point had but one official denomination -- the Catholic Church. Adding to the vitriol were still more radical elements vying for even greater reforms, not least of all the Anabaptists. Even in Zürich, Zwingli had to content with a former friend-turned-firebrand-turned-rival named Conrad Grebel. A poem of Grebel revealed his particular temperament: "Wrath and jealousy burst in bits all bishops...." By way of religious disagreement, Europe was about to add further fires to their already heated political wars. The Swiss Confederacy itself divided amongst denominational lines. Some cantons embraced Zwingli -- Basel and Bern -- forming in 1528 a Christian Civic Alliance (or League). Against Zwingli were Lucerne, Zug, Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwalden, encouraged by Johann Eck the Roman Catholic theologian. At the Second War of Kappell in 1531 Zwingli was himself killed. Many contemporaries took this as "divine judgment" that Zwingli was on the wrong path to reform. According to legend (perhaps true all the same), Zwingli died with a sword in one hand and a Bible in the other. A Swiss peace treaty was signed that same year. Each canton was given freedom of choice as to its religious denomination. That same decade the Frenchman Jean Calvin came to rule Geneva through his Consistory, which some have labeled a "Protestant Dictatorship." Despite this relative and newfound peace in the Swiss Confederacy, the wars of religion were just beginning in broader Europe. The conflicts would embroil the continent for the better part of the 1500s, especially France. Then, as the wars of religion began to subside in there, they would reignite in a central Europe in a still more explosive fashion in the 30 Years' War (1618-1648).

— Guildwater Archive —